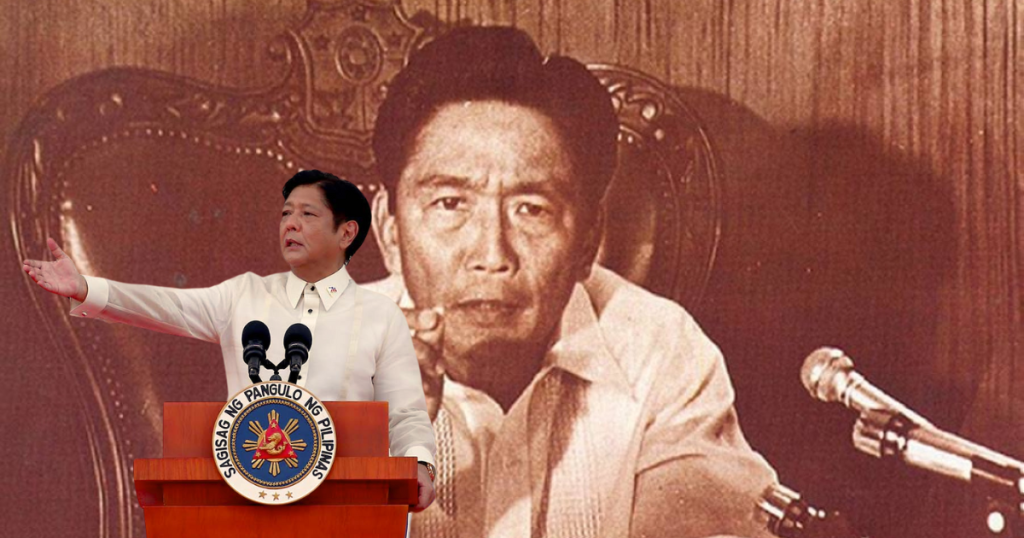

Bringing the dictator back to life

By Manuel Mogato | Date 01-19-2024

When Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos Jr ran for president in the May 2022 elections, he was on a personal crusade.

The namesake and only son of the disgraced dictator, who had ruled the country with an iron fist for almost two decades, wanted to redeem his family’s honor.

When his father was toppled from power by a near-bloodless military-backed popular uprising in 1986, the world came to know that Marcos was one of the most corrupt politicians, siphoning off $10 billion from the government’s coffers and stashing them away in Swiss banks, properties, stocks, equities, jewelry and pieces of art.

The son, known also as Bongbong, did not waste time resurrecting the Marcos legacy as soon as he won the presidency in a record manner.

Bongbong was the first presidential candidate to win a clear majority in the multi-party elections, obtaining nearly 60 percent of the votes cast in the polls.

Rodrigo Duterte, who had emerged as the country’s most popular leader, was only elected by 39 percent of eligible voters in 2016.

Bongbong knew he had a clear mandate to revise the country’s history and rehabilitate Marcos’ name.

After only a year in office, the local press has stopped referring to his father as a ruthless dictator, a human rights violator who had tortured, jailed, and killed tens of thousands of people who had openly opposed and criticized his leadership.

Suddenly, people also forgot that the Marcos family still owed the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) in unpaid estate taxes.

These were the issues that Bongbong cleverly dodged during the presidential campaign, avoiding news conferences and media interviews.

Once in power, Bongbong started picking up the low-hanging fruits to restore his father’s legacy.

He took on the agriculture portfolio to bring back his father’s failed farm policies – the Masagana 99 rice sufficiency program and the Kadiwa stores for cheap farm products.

There was an effort to re-introduce the healthy “Nutri-ban” bread in all public elementary and high schools nationwide.

He also condoned farmers’ unpaid loans under the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law, bringing back memories of when his late father had emancipated landless farmers in a land reform act.

He has also intensified the country’s labor export policy by sending more contract workers to the Middle East, Asia, and the Western world in Europe and the Americas.

His administration’s efforts to set up more specialty health centers reminded Filipinos of his mother’s specialty hospitals – the Heart Center, the Lung Center, and the National Kidney and Transplant Institute.

He also reorganized his praetorian guards, increasing the Presidential Security Command to a division-size unit with handpicked, loyal, and dedicated personnel, equipment, and assets.

Filipinos tend to forget the legacies of Marcos’s father, and succeeding leaders may change and alter these policies to make their mark.

But there is one more thing that Bongbong wanted to bring back to life – his father’s 1973 Constitution- that would effectively revert the country’s system of government to a unicameral parliament.

From 1978 to 1986, the Philippines experimented with a French-style unicameral parliamentary form of government with Cesar Virata as prime minister and Marcos as president, directly elected by the people.

It was a rubber stamp parliament dominated by Marcos’ Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) political party.

However, the revival of the unicameral parliament has a twist.

Marcos’ first cousin, Ferdinand Martin Romualdez, who headed the House of Representatives, was pushing for a Singapore-style parliament with a ceremonial president and a powerful prime minister.

That would boost his chances of succeeding his cousin, Bongbong, and keep the political family in power until the next decade.

Changing the 1987 Constitution, associated with Corazon Aquino, would cement the Marcos legacy, especially if something similar to the 1973 Constitution were in place.

That would complete efforts to bring the dictator back to life.

At the start of the year, the efforts to gather 8.3 million signatures to petition to change specific provisions in the 1987 Constitution started.

There were reports that about 400 cities and towns had already submitted the collected signatures in each of the 253 congressional districts to the local offices of the Commission on Elections.

There could be a referendum before June this year to amend Article XVII in the Constitution, putting the revision of the 1987 Charter into motion.

A new constitution could be in place before the mid-term elections in May 2025, setting aside the presidential election in 2028 to give way to a transition period extending Marcos’s term until 2031.

The new form of parliamentary government may start in 2031, perpetuating the Marcos-Romualdez political clan in power and preserving the dictator’s legacy.

Marcos’ human rights atrocities and kleptocracy would be wholly forgotten nearly half a century after his ouster from power.